TOROBAKA

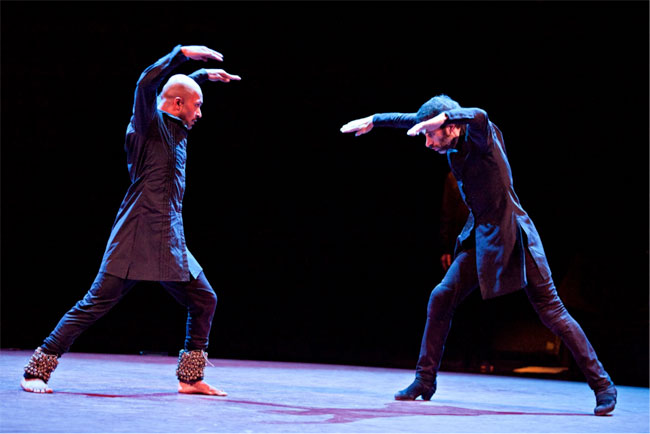

AKRAM KHAN AND ISRAEL GALVÁN

Akram Khan

“His dancing is mercurial, his characters superbly realized.”

The Independent, UK

Israel Galván

“A dancer ahead of his time, that’s for sure, as no one has ever danced this way.” El País, Spain

“Torobaka is a cultural “dance collision” of traditional kathak and flamenco with the celebrated Israel Galvan and Akram Khan. While neither can be considered ‘pure’ in their approach, they are arguably the most charismatic performers of their chosen native dance forms, which are at once distinct and deeply historically linked.

Kathak and Flamenco come together on the same stage in a showcase of virtuosity. With six musicians they will explore the similarities in their dance and, seeking to learn from each other, bring us a thrilling clash of cultures.

Created and Performed by

Israel Galván and Akram Khan

Music Arranged and Performed by

David Azurza, B C Manjunath or Bernhard Schimpelsberger, Bobote, Christine Leboutte

Lighting Designer

Michael Hulls

Costume Designer

Kimie Nakano

Sound

Pedro León

Rehearsal Director

Jose Agudo

Production Coordinator

Amapola López

Production Manager

Sander Loonen

Technical Coordinator

Pablo Pujol

Producers

Farooq Chaudhry & Bia Oliveira (Khan Chaudhry Productions) and

Chema Blanco & Cisco Casado (A Negro Producciones)

Co-produced by

MC2: Grenoble, Sadler’s Wells London, Mercat de les Flors Barcelona, Théâtre de la Ville Paris, Les Théâtres de la Ville de Luxembourg, Festival Montpellier Danse 2015, Onassis Cultural Centre - Athens, Esplanade - Theatres on the Bay Singapore, Prakriti Foundation, Stadsschouwburg Amsterdam / Flamenco Biënnale Nederland, Concertgebouw Brugge, HELLERAU – European Center for the Arts Dresden, Festspielhaus St. Pölten, Romaeuropa Festival

Sponsored by COLAS

Produced during residency at Mercat de les Flors Barcelona and MC2: Grenoble

Supported by Arts Council England

Israel Galván is an Associate Artist of Théâtre de la Ville Paris and Mercat de les Flors Barcelona

Akram Khan is an Associate Artist of Sadler's Wells London, and formerly an associate artist of MC2: Grenoble (2011-2014) when TOROBAKA was created

World Premiere: MC2: Grenoble, France, 2 June 2014

Spanish Premiere: XXXI Festival de Otoño a Primavera, Madrid, 27 June 2014

UK Premiere: Sadler's Wells Theatre, London, 3 November 2014

Akram Khan; Israel Galván; Khan; Galván; the very euphony of their names sets the scene. Dance before it became art. This transition, this intermediary space, this interstice is where they operate.

This is not, of course, an ethnic exchange between traditions, an exercise in global dance. It is about creating something from a way of understanding dance – derived, certainly, from dancing kathak and flamenco – that harks back to the origins of voice and of gesture, before they began to produce meaning. Mimesis rather than mimicry.

The hunter, lost in the countryside, imitates the gait of the animal he has come to hunt. Words are yet to be defined, guttural sounds which are understood almost as if they were orders, acts of command. Every part of the body is expressive, movements are read, they have a function. Torobaka!

Nor is there any need for primitivism. In one of the rehearsals Khan and Galván grappled with Toto-vaca, a Maori-inspired phonetic poem by Tristan Tzara. It was automatic. The bull (toro) and the cow (vaca), sacred animals in the dancers’ two traditions, but united, profaned (in the original sense of the word, to restore things to their common use), in an unconstrained dadaist poem.

Israel Galván and Akram Khan. This is what it is about, dancing without compromise and for the audience to go on perceiving it as art.

Pedro G. Romero, January 2014

Texts from Israel Galván and Akram Khan, May 2014

Master, you have shown us unfamiliar images and rhythms, a new world that I now recognise as kathak. There are poisons that heal, and kathak is one of these remedies. I have it nestled within my body.

Master, sometimes we must move forward, go faster and then stop suddenly. Gandhi, perhaps, knew that by standing still we more easily see the world than people who are always moving.

Master, I came prepared for a cockfight, the snake and the weasel, and we have become monks, two holy men in a secluded monastery of dance.

Master, I have found a brother, one and only, unique. Maybe people won't like our steps, but I have learnt so much. What matters is the process. I hope that each of our thousands of hours of rehearsals, and the work together, can be seen. I hope that all that we put into the show can be seen, and the rest too, all that we have removed. What is and what is not: everything is important.

—Israel Galván

Dancing beside Israel is like dancing next to a sublime storyteller of rhythms, not rhythms of the past, but rhythms of the future. I have gained so much insight into flamenco through Israel. He has opened my eyes into how and what is possible with flamenco: how one can deconstruct it, transform it and recreate it, in order to form new stories. After all, stories are what help us make sense of the world.

I think the simplest way to describe our process together is to imagine if fragrance was created before the flower that contains it, that's how our ideas developed on this wonderful journey. At first we created smells, colours, sketches, then together, with the musicians, lighting designer, sound designer, costume designer, rehearsal director and many others, we finally encapsulated it in the body of a theme: TOROBAKA.

—Akram Khan

Texts from Israel Galván and Akram Khan, early 2013 before starting the creation – first thoughts on what would become TOROBAKA

The Dancing Bodies of Anarchy

Tradition is like oxygen during the day, and during the night it is carbon dioxide. I would say that is the simplest way I could think of to illustrate what Israel and I do, with our respective traditions. For Israel, flamenco would be his tradition, and my oxygen would be kathak.

For many years now, I have been hungry to create a space where these respective traditions can co-exist with each other to create a new dynamic dance... But the reason I held back was simply because I was not excited to revisit what so many other artists before us have attempted, which is to simply illustrate a

connection between the two traditions.

How do we break the mould or the tradition from within? Only when I finally witnessed Israel perform, did I realize that he was the artist I was waiting for to travel on this journey of discovery and anarchy… (After all, anarchy is sometimes necessary to remind tradition to update itself.)

— Akram Khan

In Gestation

My mother danced in flamenco venues in Seville until the seventh month of her pregnancy. She was pregnant with me, I was inside.

I grew up dancing with my parents and I developed an almost religious respect towards flamenco.

I had a master whose name was Mario Maya. When I watched him for the first time I became completely amazed by new things that I had never contemplated before.

When I was training with Akram in Paris, he reminded me of my master. I asked Akram to choreograph some dance steps typical of my master. Akram picked up the steps perfectly, he felt confident with them and I could see a young Mario. The way Akram communicates whilst moving was very dear to me.

I dance barefoot but the borderline between us are my boots with toes and heels.

He told me once that when he dances, it is like giving a present to the audience. As a dancer I inherit the idea of killing the audience in order to avoid them killing me.

I think that Akram grew up believing in lots of gods. My family taught me to believe in one.

I would like to meet many of his gods and thank the audience while I dance.

— Israel Galván